[Blog updated February 2020, with thanks to Dr. Andrew Peregrine for his suggestions.]

There’s a lot of ongoing hype in the media about ticks – like this cartoon that popped up on Facebook a while back.

This kind of fear-mongering is concerning. It’s very reasonable to be informed, watchful and responsible, and quite another thing to make people afraid to go outdoors.

Tick numbers in Ontario are indeed increasing, but so far at a relatively modest rate. Climate change is driving ticks’ ability to establish further north, and certainly Lyme disease in people in Ontario has increased in the past few years, from 144 reported cases in 2009 to 624 in 2018. That’s still a low prevalence, 4.3/100,000, or 0.0043%.

I spoke to Dr. Andrew Peregrine, Professor of Parasitology at the Ontario Veterinary College, about what shelters should be aware of and what we should be doing about ticks. I’ve also drawn on several other sources, which are acknowledged below. Many thanks to Dr. Peregrine for his help!

Who are the players?

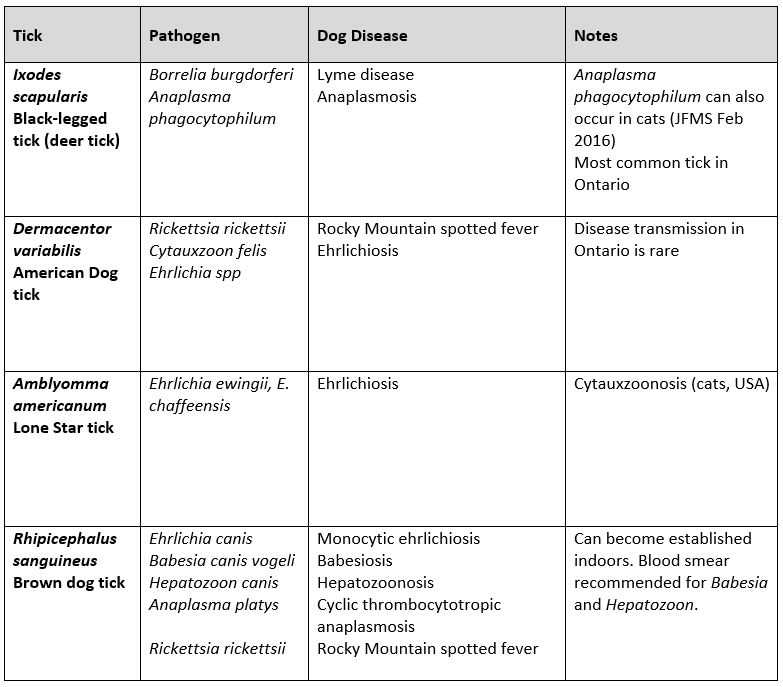

There are four ticks of practical significance for pets in Ontario. None of them transmits disease to cats within Canada [see table below; modified from 1]. Amblyomma americanum (the Lone Star tick in the cartoon) is a tick that experts are indeed concerned about, but so far it has not become established as a permanent population in Ontario. Dermacentor variabilis is unlikely to transmit pathogens here, although it does further south. Rhipicephalus sanguineus is a tick we really want to avoid. Its numbers here are tiny, but it is a significant risk when dogs are transported from endemic areas, and is the only one able to establish itself indoors. Ixodes scapularis is by far the most abundant and of greatest concern for dogs and people in Canada. Although the tick can transmit Anaplasma phagocytophilum, in Ontario this is much less common than Lyme disease.

What’s the risk of ticks and tickborne diseases in dogs in Ontario?

The overall risk is quite low, but for Lyme disease in particular, it’s increasing every year. It’s difficult to find current active surveillance figures for tick numbers (i.e. tick dragging in targeted areas, as opposed to passive surveillance, which relies on people sending ticks in for identification). Not every tick carries disease, of course, but it’s reasonable to worry more if there are more ticks around. Click the links for a recent Lyme map and canine risk assessment infographic from Ontario Animal Health Network .

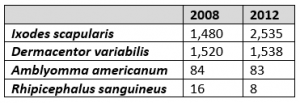

In terms of overall tick numbers, this passive surveillance study of ticks (on people) only goes to 2014. While the numbers in Ontario weren’t skyrocketing over the reporting period, it’s clear that Ixodes scapularis was on the increase [2]:

The Pets and Ticks website, launched by Dr. Scott Weese in 2016, provides a lot of information for pet owners and veterinarians, as well as maps of ticks identified through passive surveillance. It’s important to be aware that the numbers are still quite small and artificially high prevalences might show up for an area if, for example, a local shelter imports a lot of dogs from tick-endemic areas.

It’s also important to recognize that there are “hot spots” for ticks and that risk is not evenly distributed. Natural areas have higher tick numbers than urban areas. Also, parasite control for pets may be poor to non-existent in more remote or poorly resourced communities, and higher prevalences of ticks and tick-borne diseases may occur.

When transferring dogs from outside your area

It’s helpful to think about the risks of transferring or transportation, not just importation, because disease profiles can vary so vastly within Canada. Receiving shelters must educate themselves about what ticks and tick-borne diseases to expect. Before transport, all dogs should be treated with a tick product labelled for the important species of ticks. Check for ticks when animals arrive from endemic areas. Remove any ticks and identify them. Often shelters can do this in-house, using identification guides like this one. If that’s not possible, submit the ticks to a local laboratory or to the Pets and Ticks group.

There are several excellent tick products available for dogs in Canada. Products effective against the 4 important ticks in the table above are afoxolaner (Nexgard), fluralaner (Bravecto), sarolaner (Simparica) and imidacloprid/permethrin (K9 Advantix) and lotilaner (Credelio). (Note that only Simparica and Credelio are currently labelled for all 4 species in Canada.) There is now also a labelled topical Bravecto product for cats in Canada, which will probably be used more for mites than for ticks. See our blog on demodicosis for more information about the isoxazoline (“-laner”) tick products.

Testing for tick-borne diseases

Many shelters automatically run 4DX Plus or similar tests on dogs with ticks, or dogs from tick-endemic areas. That’s not a bad idea, but Dr. Peregrine emphasizes that shelters should only test if they are clear about what the results mean (and don’t mean!) and what they will do with them.

- Positive test for Borrelia burgdorferi: This is an antibody-positive response and tells you the dog has been exposed to the Lyme spirochete, but not whether it will develop clinical signs. 95% of Lyme-positive dogs never develop clinical signs so a positive test alone is not an indication for treatment. Only clinically affected or proteinuric dogs require treatment.

- Positive test for anaplasmosis: This test detects antibodies to A. phagocytophilum and A. platys, and again detects exposure, not disease. Unlike Lyme, which has a long incubation period, anaplasmosis will cause clinical signs within 1-2 weeks, so if the dog is not sick at the time of positive testing, it’s unlikely to develop clinical signs. For dogs requiring surgery, a CBC is recommended to rule out thrombocytopenia. Some shelters may choose to run a CBC on all positive dogs, given that thrombocytopenia can be clinically silent.

- Positive test for ehrlichiosis: This test detects antibodies to E. canis and E. ewingii. The onset of clinical signs is 1-3 weeks, and the disease can be severe and potentially fatal in some cases. A CBC is helpful, as for anaplasmosis.

- Positive test for babesiosis: Sorry, that’s a trick one! A blood smear or PCR is needed to diagnose this parasite. Keep it in mind when dealing with dogs from a Rhipicephalus sanguineus– endemic area.

Should shelters test ticks for diseases?

Short answer, no. More at Worms and Germs.

References and Resources

- Quick Reference: Ticks and Pathogens Drs. Scott Weese, Katie Clow and Michelle Evason

-

Ticks and Lyme Disease in Ontario: What’s the real risk? This is an excellent infographic showing prevalence and the risk of infection for a dog that is bitten by a tick.

- Tick removal instructions

- ACVIM consensus statement on Lyme borreliosis in dogs and cats – 2018 update

- Professor Peregrine’s talks on tickborne diseases, CASCMA CPD Day November 2017 – CASCMA archive