Neonatal l kittens (0-2 weeks old) are our most vulnerable and fragile patients. Increasingly, shelters are able to help and save these kittens.

One could reasonably make the point that “neonatal kittens are not small adult cats”! Here are some of the ways they are unique, and how we can tailor our medical care to their special needs.

Body weight: An essential measure

Normal birth weight for kittens is 90-110g. Low birth weight is an important predictor of survival.

In the early weeks, kittens should gain an average of 10-15g per day.

Weight is an objective and reliable measure of how a kitten is doing. Failure to gain weight for several days, or sudden weight loss, is always an indicator of trouble.

Nursing: Watch out for too much of a good thing

It may seem really obvious, but kitten carers often think that if a kitten is constantly nursing from the queen, all must be well. In fact, kittens should not be nursing most of the time. If they are, it’s a sign they are not getting enough milk.

Hypothermia: A treatable and avoidable killer

Normal body temperature for neonates is only 36-37 C.

They lose heat easily and can only stay about 6 C warmer than their environment.This has tremendous implications for orphans. Keeping them warm enough is absolutely vital.

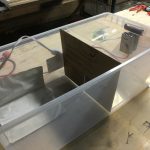

A large tote can be rigged up as an incubator, using electric warming pads designed for people. The incubator temperature should not be above 32C, and the kitten needs to be able to move off the heat source. Ensure there are holes in the lid of the totes to allow moisture to escape. The use of a thermostat and thermometer is highly recommended. Technically these warming pads are not meant to be used for this purpose and there are lots of warnings that go with them. Caveat emptor.

.

.

DIY kitten incubator (Courtesy: Linda Jacobson, Toronto Humane Society)

Kitten reflexes

Absence or weakness of these basic reflexes, necessary for survival, are indicators of serious trouble.

- Righting response – place kitten on its back on a towel and release. The kitten should be able to right itself quickly.

- Rooting response – allow the neonate to push its muzzle into circled fingers. It should push strongly forward

- Suckle response – Gently insert a finger, syringe tip or teat into the mouth. The kitten should suckle automatically

Drug dosing in neonates

Liver and kidney function are immature up to 6 weeks of age, so drug metabolism is impaired. Don’t bother looking for dosing studies – nobody has done them. There are really two general guidelines:

- The more toxic the drug, the less suitable it is for kittens. Drugs with high margins of safety, such as penicillins, are suitable for kittens whereas those with low margins, such as aminoglycosides, are not. For drugs with intermediate safety that have to be given, dilute 1:10 for accurate dosing.

- In general, especially for drugs with intermediate safety, give 30-50% of the adult dose. Increase the dosage interval if the drug is excreted renally.

Lab work in neonates

A practical MDB for a sick kitten could include blood smear to estimate the WCC, ear prick for blood glucose and urinalysis or USG. For older kittens, PCV/TP is feasible and chemistry can be done using a 0.7mL heparin chamber. Refer to normal values for kittens, because many values are very different from adult cats.

Crashing kittens

Critically ill kittens typically have hypothermia, hypoglycemia and/or dehydration. All must be addressed, starting with hypothermia.

Kittens are “not dead unless warm and dead”. Always rewarm SLOWLY over 1-4 hours. Sudden rewarming causes fluid loss and a sudden increase in oxygen demand, and can lead to cardiovascular collapse and death.

Weight loss is the best measure of dehydration. Skin tent is unreliable because skin is not elastic due to low amounts of fat. USG > 1.020 is suspicious for dehydration. Kittens have a large surface area relatively to body size and poor urine concentration (SG < 1.020). Fluid requirements are 2-3 times those of adults i.e. 80-120mL/kg/24 hours.

In really tiny kittens, IV access is rarely feasible. Warm SQ fluids can be given and for those of us old or brave enough, the IP route is an option too. Intra-osseous fluids can be given but this is painful and the risk of infection is high. Don’t forget the oral route. Only give oral fluids or dextrose after the kitten has been warmed. Hypothermia can reduce intestinal absorption and anything given orally can then result in diarrhea, making matters worse.Oral electrolyte replacement can be a life-saver, though, once warming has taken place. Remember, stomach capacity is only 5mL/100g.

The colours of kittens (mucous membranes and stool, that is)

Mucous membranes:

- Hyperemia is normal for kittens < 7 days – thereafter their mucous membranes should be pink and hyperemia in kittens > 7d can signal dehydration

- Sick kittens can be pale or cyanotic

- Septicemia is a common end result of many conditions. Clues are weakness, crying, cyanosis or hyperemia, and purplish discoloration of the extremities. Dyspnea may be seen in late-stage sepsis.

Stool:

- Normal neonate stool is yellow or tan colour, with a toothpaste consistency

- Yellow/green watery stool is a sign of overfeeding

- Blood in the stool can indicate coccidiosis, sepsis, parvo, E.coli or Salmonella infections

X-rays in kittens

Reduce KVP by 50% because the low fat percentage results in low contrast. Always X-ray a sibling for comparison where possible, because kitten X-rays can be difficult to interpret.

Key Sources:

- Critical care of the sick neonatal kitten. Dr. Elizabeth Thomovsky, Maddie’s webinar 2014; http://www.maddiesfund.org/critical-care-of-the-sick-neonatal-kitten.htm

- Feline Pediatrics: How to Treat the Small and the Sick. Dr. Susan Little, Atlantic Coast Veterinary Conference Proceedings 2012 (available on VIN)

- Critical and Supportive Care in Pediatrics. Dr. Anthony Abrams-Ogg, Western Veterinary Conference Proceedings 2003 (available on VIN)