July 5, 2020

There’s been a recent groundswell of support for face masks in Canada and the US. Many Ontario jurisdictions have recently mandated face coverings in public indoor settings. Quite a number of political figures in the US, who previously did not support mask-wearing, are now appearing in public wearing masks, and supporting or even mandating their use.

The debate in Canada has, thankfully, not been nearly as polarized or politicized as that in the US – yet my Twitter feed is peppered with a surprising number of people who feel passionately that mandating masks is unnecessary, or undemocratic, or both.

I got to thinking about this – in particular, about the evidence for wearing masks in public. Is there really evidence for benefit, or are we just “sheeple”, desperately clutching at a new straw in another manifestion of groupthink?

Specifically: Is mask-wearing by the general public likely to help reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to an R0 of below 1? (Meaning that one infected person will infect less than one other person.)

I’m guessing that a lot of other people are wondering the same thing(s). So, here goes:

Levels Of Uncertainty And Risk Remain High

There are still high levels of uncertainty around critical aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic. We still don’t know the precise contribution of aerosol droplets, airborne infection (tiny droplets) and contaminated surfaces in virus transmission. That seems incredibly basic, but it happens to be very difficult to tease out. (There is growing scientific consensus, however, that the most important mode of transmission is aerosol droplets, followed by airborne transmission, followed by fomites.) We don’t know how long immunity lasts. We don’t know how many people have really been infected. We don’t know what the Fall is going to look like, or next year.

Here’s what we do know:

- COVID-19 is a global public health emergency that is nowhere near controlled. Case numbers and fatalities are rising rapidly in many parts of the world.

- Governments and public health agencies have no choice to but make decisions in the face of risk and uncertainty. Those decisions need to take into account what is known, what can reasonably be assumed, and the risks of making or not making that particular decision. They also, unavoidably, need to take into account political and economic costs and risks. (This blog largely presupposes that decisions are not malign and are largely reliant on science, which is certainly true in many places. Where they are malign, or anti-science, there are a lot of other problems to deal with.)

- Public health decisions won’t always be right first time. We don’t have the luxury of waiting around for perfect data.

- In the absence of a vaccine, cure or widespread population immunity, we remain reliant on non-pharmaceutical interventions to reduce viral transmission.

We seem to have stopped talking about flattening the curve, but that’s still what we’re doing. We’ve got it pretty flat in Canada, and we need to keep it that way.

Why Is There So Much Confusion About Face Masks?

Early messaging was that cloth masks were not likely to protect the wearer and that more effective masks should be reserved for first responders and healthcare workers. The Centers for Disease Control then recommended face masks in public places, especially when social distancing can’t be maintained, as early as April 2.1 But the World Health Organization only made the recommendation on June 5. That gap has created a lot of confusion.

Then there’s the confusion in Ontario, with local jurisdictions having to mandate masks in the absence of a provincial mandate. That means, among other things, that the TTC requires masks while Go Transit currently does not. (Presumably the virus stops at the junction between your Go Train and your Toronto streetcar.) I’ve already mentioned the politicization of mask wearing. For some adherents, this is an ideological issue. There are those who will fight to the death (of someone) for the right not to protect other people.

Should we blame our leaders for these mixed messages? Not really (unless their motives are malign, see above). They’ve mostly been doing the best they can, in a complex environment. Don’t forget, one of the early reasons that universal mask-wearing was not recommended was to preserve masks for medical personnel. That’s only changed because production has ramped up, but it still applies to N95 respirators, which you and your friends should not be wearing.

Summary of the main reasons for confusion:

- Mixed messages from authorities and the media;

- Mixed or missing evidence for effectiveness of masks, particularly cloth masks;

- Unavoidable changes in policy as the pandemic evolves;

- A belief by some people that re-opening means that the pandemic is winding down, so we should be reducing precautions, not ramping them up;

- The misconception that reasonable public health precautions are politicized assaults on freedom.

So – what is the evidence for cloth face masks in public settings? Not so fast.

It’s important to be clear on what we are talking about. Most published studies regarding the efficacy of masks have been (1) in healthcare settings; (2) about protecting the wearer; and (3) about medical-grade masks or respirators, which are tested and standardized (unlike cloth masks). The central question around public mask-wearing is not about protecting the wearer, but about reducing transmission – in other words, source control, or protecting other people. So it turns out that much of the previous evidence just doesn’t relate to the issues here.

Also, the tests of how efficiently different masks filter viruses usually use particles of sodium chloride, to emulate viruses, and don’t look at how good the masks are at stopping the aerosol droplets that are thought to be the main means of transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Another problem – the highest standard of medical evidence is the randomized controlled clinical study. That’s usually not possible, ethical or appropriate on a population level, or in a public health crisis. The closest we get to controlled studies are the giant “experiments” that have taken place in different countries and jurisdictions – taking into account that there are a large number of other variables that also influence outcomes.2

Do we know anything at all about the efficacy of masks in public? Yes, actually, we do.

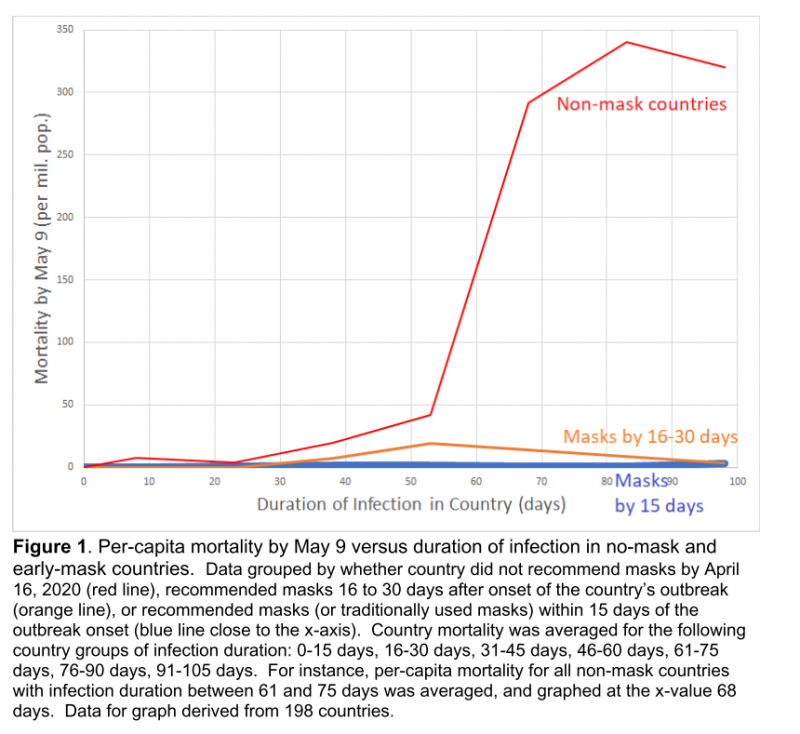

A multivariable model of 161 countries found that public mask use independently predicted lower mortality.3 Mortality was markedly different between countries where masks were the norm and where they were not. The authors state: “Even if one accepts that masks would only reduce transmissions by 22%, then after 10 cycles of the infection, mask-wearing would reduce the level of infection in the population by 91.7%, as compared with a non-mask wearing population.”3

There’s a lot more in that vein – see suggested references below. But they say a picture’s worth a thousand words, so here’s a little visual guide:

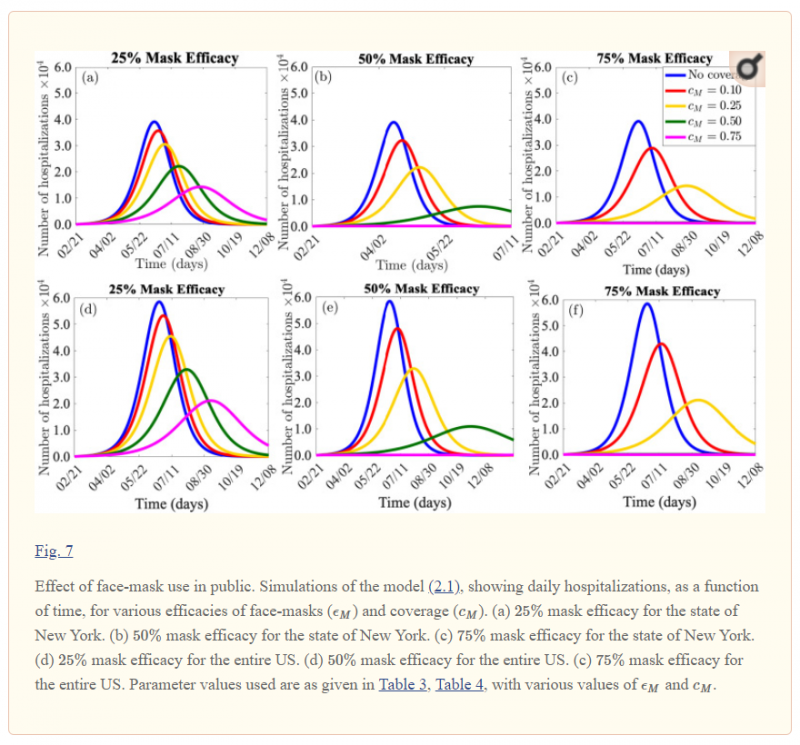

These graphs from a modelling study show a dramatic difference in hospitalization rates when masks are used by a high proportion of the population.4 Bear in mind that modelling studies are based on a lot of assumptions.

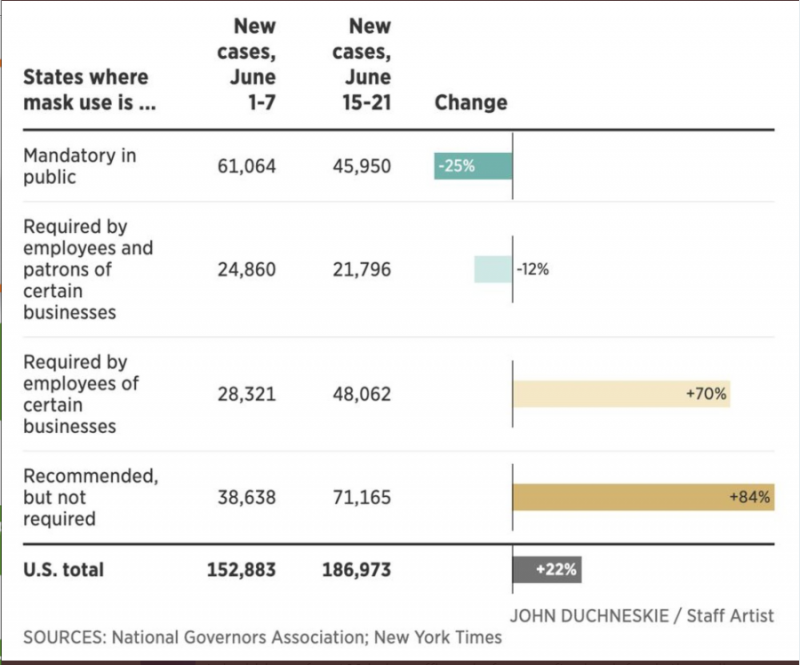

Here’s a composite graph from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, showing infection rates in US States where masks are and are not mandatory:

This graph should get everyone’s attention. It compared per capita mortality between countries that did and did not recommend masks early:

And this is a very cute graphic that really gets the message across:

Wait a minute, what about this study?

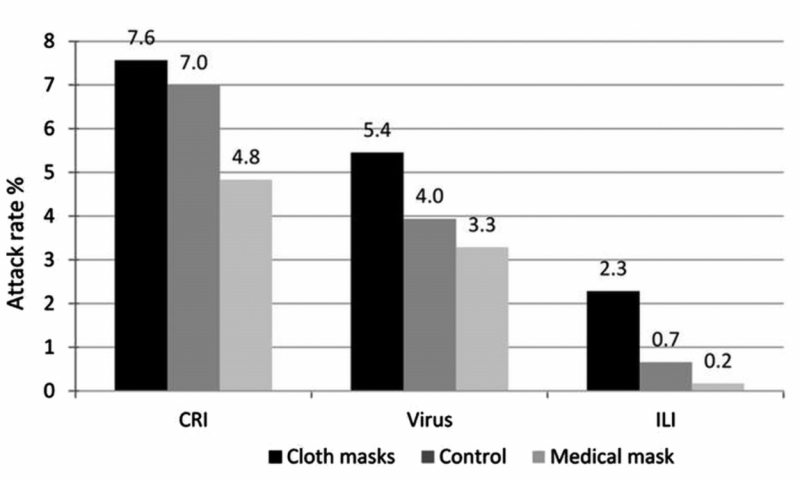

There is no unanimous body of evidence in science. This 2015 study that could be used to show that masks don’t work. The randomized study of cloth masks, compared with medical masks, showed a significantly increased rate of respiratory infection among healthcare personnel wearing cloth masks.7 The “control” group here were asked to do what they would normally do, which unfortunately included a high rate of mask use. That means there was no “no-mask” control group. However, compliance with mask-wearing was lower in the control group. There was very poor filtration by the cloth masks, which allowed 97% of virus-sized particles to penetrate compared with 44% for medical masks. The authors of this study suggested that wearing cloth masks in this setting may have been actively detrimental and that they should not be recommended for healthcare workers.

Virus = laboratory-confirmed viral infection

ILI = influenza-like illness

Source: MacIntyre7

The study was, of course, not about COVID-19 and was about protection of the wearer, not the other person. But I’ve included it because it should give us pause. Maybe cloth masks really aren’t very helpful. We can’t know with 100% certainly and we shouldn’t recklessly write off studies that don’t show that masks reduce COVID-19 transmission. We can, however, easily disregard J. Random Twitter User who has an uninformed opinion based on their echo chamber or their misguided ideas about their personal freedom compared with the other person’s right to survive.

Public health officials will continue to review the data as they come in, and in most jurisdictions, policy-makers will make reasonable decisions in good faith. In the interim, it is overwhelmingly likely, based on the preponderance of evidence, that cloth masks substantially help to reduce community transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

More studies

As the title states, this is by no means intended to be a systematic review, so here are more sources of original data for those who are interested, or still skeptical:

- To mask or not to mask: Modeling the potential for face mask use by the general public to curtail the COVID-19 pandemic8

- Comprehensive review of mask utility and challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic9

- Estimation of effects of contact tracing and mask adoption on COVID-19 transmission in San Francisco: a modeling study10

- Impact of population mask wearing on COVID-19 post lockdown11

- Face mask use in the general population and optimal resource allocation during the COVID-19 pandemic12

- Masks4Canada Resources 13

- Centers for Disease Control Resources 1

- Brief research report: Bidirectional impact of imperfect mask use on reproduction number of COVID-19: A next generation matrix approach15

- For a robust exchange of views, see Greenhalgh14 – the opposing viewpoints are also outlined in this review.

What is the general consensus and understanding of the impact of cloth masks in public?

- Cloth masks appear to have modest to reasonable efficacy for trapping large aerosols and thereby reducing the number of virus particles that get out to infect other people;

- They offer limited, but not zero, protection to the wearer;

- If both people in an interaction are wearing masks, the protection is likely to increase non-linearly;

- Adding face shields to masks markedly improves the level of protection for both the wearer and the other person;

- Countries and juridictions where universal mask-wearing is common, or was mandated, have had substantially lower rates of transmission and mortality than countries where mask wearing is sporadic, or limited to symptomatic individuals.

We’ve flattened the curve in Canada. Crushed it! So why are we suddenly getting excited about masks?

The timing makes a ton of sense when you stop to think about it. Masks have little impact on community transmission during strict stay-at-home orders, but become critically important as society opens up again. Having flattened the curve in Canada, we now have a narrow window during which we can continue to control infection rates – through that all-important R number.

If we don’t work hard to reduce transmission, we’ll see a substantial resurgence of cases. Simple as that. There’s incontrovertible evidence, all over the world, that this is inevitable, unless clear and stringent precautions are put in place.

When thinking about the argument for public mask-wearing, it’s important to consider that a large proportion, possibly around half, of people who are shedding SARS-CoV-2 are asymptomatic or presymptomatic. So just trying to be responsible and stay home when sick is nowhere near enough. You might be infected and be out in public infecting other people, without having any idea you’re doing it. You might never know, if you’re one of the really lucky ones. But other people who were near you might not be so lucky and could end up in ICU, on a ventilator, or worse.

So – we’re getting excited about masks right now because they are an important adjunct to other measures and can make a substantial difference in transmission.

Should masks be substituted for other measures?

Here’s where danger creeps (or rushes) in. With all the enthusiasm for masks, it becomes possible for policy-makers to remove other protections. Messaging blurs, and people start thinking that wearing a mask is all they need to do. Airlines and transit systems like the TTC are trying to substitute masks for physical distancing. That’s like suggesting the rhythm method over abstention or the Pill. Just won’t cut it.

Cloth face masks aren’t enough on their own. They are an adjunct to other measures – staying home as much as possible, limiting contacts, isolating yourself when ill, quarantine after possible exposure, physical distancing, COVID screening, hygiene measures, testing and contact tracing. We need them all.

Downsides of masks

What are the disadvantages of masks? There are a few, but none that preclude their use. This just requires some education and common sense:

- A false sense of security. Educate, educate, educate. Wishful thinking is not our friend. This is probably the greatest “danger” of public mask-wearing. First, that it allows public policy-makers to remove other, more important measures. Second, that it encourages people to take more risks than they would otherwise, in the mistaken understanding that non-medical masks will protect them. It’s so important to remember that masks primarily protect other people. Keep your distance from that other person.

- People don’t wear them properly. Yes, that’s true, but it can be overcome through education, not everyone has to do it right, and it’s no reason not to mandate masks.

- Environmental contamination, more waste. Cloth masks are reusable. Even medical-type masks can be re-used multiple times. We hang ours on hooks at home and re-use them after 5 days if they aren’t visibly damaged. People shouldn’t throw disposable masks (or anything else) on the ground and leave them there!

- Not everyone can wear them. That’s fine. Some people genuinely can’t wear a mask in public for some reason. A small proportion of the population not wearing masks will not affect their overall efficacy.

- They cause hypoxia, etc., etc., in normal people. Not true, as any medical professional can tell you. This is a red herring.

- They are gross and uncomfortable. So is being on a ventilator. So, especially, is being on a ventilator because someone else didn’t want to be mildly inconvenienced. Get over it.

- Not everyone can afford them. Give some away and pressure your local authority to provide them in low-income areas and key locations. The TTC is giving away a million masks. Good for them.

- Masks are in short supply in my area. Prioritize places where they are most needed and risk is highest, such as hospitals, homeless shelters and long-term care facilities. Do some sewing. Even I was able to produce some good masks, and they are colourful, too!

What’s better – medical masks, cloth masks or face shields?

That’s a pretty easy one. In terms of efficacy for filtering out particles, N95 respirators > medical-grade masks > other medical-type masks > cloth masks. Face shields are slightly more complicated – they are impermeable, so they prevent any direct passage of aerosol droplets but they allow droplets to go around them because the sides are open. So they are best used as an adjunct to face masks in higher-risk situations.

Should animal shelter staff routinely wear masks in the shelter or clinic?

Short answer, yes. Here is Dr. Scott Weese’s thoughtful take on this issue in the context of veterinary clinics, back in early April.6 The Toronto Humane Society mandated masks in the shelter some time ago – see infection control protocol in our toolkit. Many shelters will have no choice but to mandate masks once they become mandatory in their jurisdiction; but it’s important to support this measure, not just comply half-heartedly.

As Dr. Weese points out, it’s very important to remember that masks are not a cure-all. “Wearing masks all the time while becoming lax at other critical practices (e.g. social distancing, hand hygiene) is counterproductive. Masks should be approached as something to use when social distancing isn’t possible, not as a means to avoid social distancing.” It’s critically important to communicate this to our staff.

It’s also important to ensure that staff understand the limitations of masks. When close contact is required over a prolonged period, face shields should be added and/or surgical masks should be used instead of cloth masks, depending on the specific situation.

Here is a link to Dr. Weese’s new blog on fomite transmission and mask use.15

Sources:

1. CDC. Considerations for Wearing Cloth Face Coverings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover-guidance.html (2020).

2. Lyu W, Wehby GL. Community Use Of Face Masks And COVID-19: Evidence From A Natural Experiment Of State Mandates In The US. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020; 101377hlthaff202000818.

3. Leffler CT, Ing EB, Lykins JD, et al. Association of country-wide coronavirus mortality with demographics, testing, lockdowns, and public wearing of masks. medRxiv 2020; 2020.05.22.20109231.

4. Ngonghala CN, Iboi E, Eikenberry S, et al. Mathematical assessment of the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on curtailing the 2019 novel Coronavirus. Math Biosci 2020; 325: 108364.

5. Chung E, CBC News. Mandatory mask laws are spreading in Canada, https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/mandatory-masks-1.5615728 (accessed 3 July 2020).

6. Weese JS. Routine mask use in vet clinics? Worms & Germs Blog, https://www.wormsandgermsblog.com/2020/04/articles/miscellaneous/routine-mask-use-in-vet-clinics/ (2020, accessed 3 July 2020).

7. MacIntyre CR, Seale H, Dung TC, et al. A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e006577.

8. Eikenberry SE, Mancuso M, Iboi E, et al. To mask or not to mask: Modeling the potential for face mask use by the general public to curtail the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Dis Model 2020; 5: 293–308.

9. Tirupathi R, Bharathidasan K, Palabindala V, et al. Comprehensive review of mask utility and challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Le Infez Med 2020; 28: 57–63.

10. Worden L, Wannier R, Blumberg S, et al. Estimation of effects of contact tracing and mask adoption on COVID-19 transmission in San Francisco: a modeling study. medRxiv 2020; 2020.06.09.20125831.

11. Javid B, Balaban NQ. Impact of Population Mask Wearing on Covid-19 Post Lockdown. Infect Microbes Dis; Publish Ah. Epub ahead of print 2020. DOI: 10.1097/im9.0000000000000029.

12. Worby CJ, Chang H-H. Face mask use in the general population and optimal resource allocation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Preprints. Epub ahead of print 2020. DOI: 10.1101/2020.04.04.20052696.

13. Masks4Canada Resources – https://masks4canada.org/resources/ (accessed 3 July 2020).

14. Greenhalgh T. Face coverings for the public: Laying straw men to rest. J Eval Clin Pract 2020; 1–8.

15. Fisman D et al. Brief research report: Bidirectional impact of imperfect mask use on reproduction number of COVID-19: A next generation matrix approach. Inf Dis Modelling in press, online 4 July 2020

Blog by Linda Jacobson DVM MMedVetPhD, Toronto Humane Society